The History of Kenya

The History of Kenya

Kenya has been populated by people for a very long time. Some of the oldest human remains are found in the country. However, Kenya’s written history is short, with a great difference between the coast and the interior. The written sources about the coast cover early periods, while the history of the inland is largely based on written sources in the archives of the colonial period.

In the late 1800s, Britain began to take an interest in the area. At the Berlin Conference of 1884, when the European colonial powers divided Africa between them, Britain secured Kenya. In 1894 an East African Protectorate was established, and in 1920 the colony of Kenya was formally established.

The British colonial era is best remembered in Kenya for hard-handed handling of the Mau Mau rebellion in the period 1952–1956. Kenya gained internal autonomy in 1963 and became an independent republic the following year.

In the period up to 1982, Kenya had a kind of multi-party system, but in reality one party dominated: Kenya African National Union (KANU). In 1982, Kenya became a one-party state. Democratization started in 1991.

Older history

Rich archaeological finds, especially in the Rift Valley, have shown that human-like species from prehistoric times have lived in the East African inland more than two million years ago. The findings have fueled the theory that it was in this area that the cradle of men stood.

Today’s population in Kenya is a result of multiple immigration, which led to the rise of long-term farmers at the beginning of our era: migration has to a certain extent taken place in modern times. Unlike in West Africa, large empires were not established in this area, but small, self-sufficient communities.

In the first hundred years of our era, several Arab trading communities grew on the coast. Persian traders also visited the coast. This trading business created important centers in Mombasa, Malindi and the islands of Lamu and Pate.

Important commodities were ivory, rhino horn, gold, shells and slaves. The Kenyan coast developed economically, was influenced by Arab culture and Islam, and the East African Swahili culture was created here and further south.

Portuguese and Arab competition

The Arab trade was exposed to competition from the Portuguese from around 1500. They invaded the coast of East Africa and invaded Mombasa in 1505. Arabs and Portuguese quarreled for power over the next couple of hundred years; the struggles significantly affected the Africans and their urban communities along the coast. The Portuguese made Mombasa a local powerhouse, and built Fort Jesus as its most important fortification in Kenya.

The fort and town were conquered by the Arabs after 33 months of siege in 1698; a few years later the Portuguese left Kenya and the coast was ruled by Arab sultans.

In 1822, the Sultan of Oman, Sayyid Saïd, sent a military force to East Africa claiming all the Swahili dynasties along the coast, but several refused to give up power and asked Britain for help. The British also fought the slave trade, which was still widespread along the coast.

The colonial past

Britain occupied Mombasa in 1822 and made the city a protectorate, which was abandoned after three years. The Sultan of Oman moved his court to Zanzibar and in 1877 offered the company Imperial British East Africa a license to administer East Africa. In 1895, Kenya was proclaimed to the British Protectorate, British East Africa, substantially to secure the road to Uganda, on the road between Cape and Cairo.

In 1902, after the railroad between Mombasa and Lake Victoria was completed, the British government encouraged white immigration and settlement in the Kenyan highlands. The whole of the fertile highlands was set aside for whites, who had significant influence over the rule of the colony, while Africans were assigned to reserves, with less and less land – and without political co-determination or influence. With the development of railways and trade, the Asian population of the country also increased.

The border between the future states of Kenya and Uganda was adjusted in 1902, and Kisumu was added to Kenya. In 1907, a legislative assembly was established in Kenya, with white dominance and a small Asian representation, but no African. In the same year, the British colony administration was moved from Mombasa to the new city of Nairobi.

World War I was also fought in parts of Africa, and in Kenya about 200,000 Africans were recruited into the British army – of which a quarter died. During and after the war, the white population strengthened its control of power in Kenya, and laws and tax rules were adopted that aimed to provide cheap African labor to the white large farms, which essentially produced goods for export, especially coffee.

This development was met with armed African resistance, especially in the Highlands. In 1921, Kenya’s status was changed and the area became a British crown colony. In 1925, a system of governing councils was introduced among Africans, essentially to stifle the emerging political organization against white settler rule.

The first African nationalist organization of importance, the Kenya African Union (KAU), was formed in 1944; before that, the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) was formed in 1924. Trade unions also grew, especially on the coast. Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, was active in both the KCA and KAU.

Kenya participated in World War II on the Allied side against the Italians in Ethiopia and Somalia. After 1945, African nationalism and the struggle for independence increased. Resistance to the settler regime was strongest among the Kikuyu people, who had been deprived of much of their land and had consistently high education.

The Mau Mau Rebellion

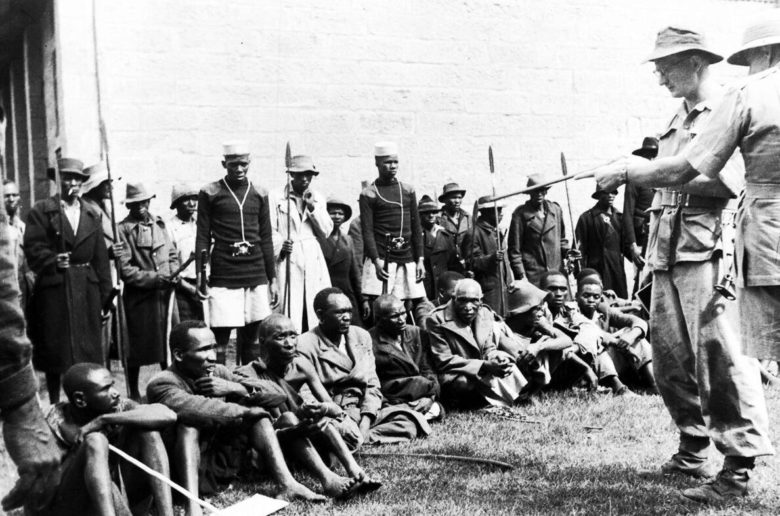

People suspected of belonging to the rebels (sitting) are being held captive by representatives of the colonial power and the local police. Photo from 1953.

In 1952, the British declared a state of emergency in Kenya after the so-called ” Mau Mau” uprising broke out. This was associated with a great deal of mystery and misleading representations, but was essentially a guerrilla war for the right to land and self-government, organized by the Kenya Land Freedom Army (KLFA). Both in contemporary and in retrospect, the rebellion was portrayed as a terrorist campaign against the whites in the country – and the rebels were subsequently treated, including through extensive use of concentration camps.

The United Kingdom deployed large forces to fight the rebellion, which was defeated by the end of 1956. About 13,000 Africans were killed and about 80,000 detained. One of these was Jomo Kenyatta, who in 1947 took over as head of the KAU, and who was also considered to belong to the leadership of the KFLA. The guerrilla’s chief leader, Dedan Kimathi (1920–1957), was captured in 1956 and executed the following year.

The road to independence

During the 1957 legislative elections, access to African members was also opened, and approximately 60 percent of the adult African population gained voting rights. After the uprising, a new land law was passed, giving Africans access to more land, including in the highlands, where a white emigration had begun. In 1960, about 60,000 whites were living in Kenya.

Following a constitutional conference in London in 1960, the Kenya African National Union (KANU) was formed. This and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) competed in the 1961 election, which gave a majority to KANU. However, the party refused to form government before Jomo Kenyatta was released, which he did in August 1961. He then took over the leadership of KANU. New elections were held in May 1963, with KANU winning again, and with Kenyatta as prime minister when internal self-government was achieved in June.

On December 12, 1963, Kenya became an independent state. The following year, the country was declared a republic, with Kenyatta as president. KADU had then disintegrated, and in practice Kenya became a one-party state led by KANU.

Independence

Jomo Kenyatta was the country’s leading nationalist leader and first president. In the colonial era, Europeans looked upon him as a radical politician, but his strong presidential rule became a guarantee of a close relationship with the Western powers. The picture shows Kenyatta with dancers from the kikuyu people on Kenyatta Day 1974.

The opposition to British colonial rule was led essentially by people from the Kikuyu and Luo peoples; the Kikuyu from the Highlands and the Luo from Lake Victoria. After independence, these continued to dominate political life in Kenya, including at the expense of the Muslim coast.

The relationship between different tribes played an important role in Kenyan politics until the 1990s, and still ethnic differences have been one conflict dimension. Another has, to some extent, been more ideologically conditioned, between conservative leaders and more radical and reformist – also within the soon-to-be-ruling party KANU.

Unlike many other countries that underwent an armed liberation struggle, the liberation struggle in Kenya did not lead to a fundamental radicalization, nor to a foreign policy orientation towards the socialist states. Ruled by conservative leaders, Kenya remained a conservative state in a partially radical Africa.

The close contact between Kenya and the United Kingdom continued after independence, and in 1964 President Kenyatta sent British forces to quell a burgeoning revolt in the wake of the Zanzibar revolution. In March of the same year, he signed a defense agreement with the United Kingdom. By independence, KANU emerged as a radical party, but soon developed in a conservative direction.

The left wing leader, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, left KANU in 1966 and formed the Kenya People’s Union (KPU). In 1969, KPU was banned, and Odinga and other party leaders were arrested. In 1969, Odinga’s political opponent in KANU, trade union leader Tom Mboya was murdered, after which KPU was banned and Odinga placed under house arrest. At the parliamentary elections that year, only KANU members could vote.

Kenyatta was re-elected to his third five-year term in 1974 and then made a lifetime president. At the parliamentary elections, only KANU members could again vote. For the next two years, Kenya suffered an economic and political crisis, with increasing political violence and accusations of public corruption. Criticism against Kenyatta’s rule and kikuyu dominance in social life grew, but was suppressed.

Jomo Kenyatta died in 1978 and was succeeded by Vice President Daniel Arap Moi. He did not belong to any of the two groups that dominated Kenyan politics, but Kalenjin, a smaller group. Despite political liberalization just after Kenyatta’s death, Odinga and other former KPU members were refused to stand in the parliamentary elections in 1979. The following year, Moi joined KANU.

The one-party State

In 1982, the myth of politically stable Kenya broke down as groups from the country’s air force tried to seize power in a military coup. The coup was knocked down, about 3,000 people taken into custody, the air force disbanded and the university closed. The coup makers cited corruption and lack of freedom in the country as reasons why they were trying to seize power. Kenya was formally made a one-party state. In 1982, Daniel arap Moi was re-elected president, but from the mid-1980s opposition to and criticism of Moi’s rule grew, partly because of the detention of critics and the limited freedom of expression.

A leading force in the resistance against Moi and KANU from 1983 was the radical grouping Mwakenya, which gathered large parts of the opposition behind it. Moi was re-elected – without a candidate – in 1988, but opposition was further strengthened by the early 1990s, not least after President Moi halted plans to introduce multi-party systems in the country, on the grounds that this would lead to increased tribal opposition.

Democratization

As in a number of other African countries, a process of democratization was also started in Kenya around 1990. Despite the introduction of multi-party government, President Moi and KANU remained in power for a long time. This was mainly because the opposition was divided, both between people and parties, and that the government controlled much of the country’s media.

In the early 1990s, several of Kenya’s aid recipients demanded the introduction of democratic governance. The criticism was particularly directed at human rights violations. At an international conference of aid providers in 1991, all new aid to the country was withheld. The conditions for resuming aid were political and economic reforms over the next six months. In December 1991, Moi gave in and allowed free political activity.