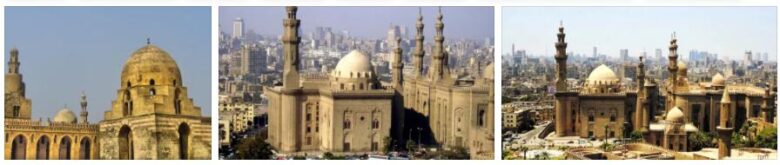

Islamic Cairo (World Heritage)

Cairo’s old town is the spiritual center of the Islamic world with hundreds of mosques and numerous Koran schools. The landmark is the citadel from the 12th century. The foundation stone for Islamic Cairo, Misr el-Kahira (“the victorious”), was laid by Fatimide Gaurhar in the 10th century. The Mehmed Ali Mosque (Alabaster Mosque) with its 80 m high minarets is one of the highlights, as is the El Nasir Mosque, the Ibn Tulun Mosque, the Sultan Hassan Mosque and the Shagarat el-Du mausoleum Islamic architecture.

Islamic Cairo: Facts

| Official title: | Islamic Cairo |

| Cultural monument: | Old city of Cairo, once the center of the Islamic world, including with the citadel, partly built of stones from smaller pyramids of Memphis, the Mohammed Ali mosque (alabaster mosque) with 80 m high minarets, the El Nasir mosque, the pentagonal Sultan Hassan mosque with almost 82 m high minaret, the Rifai Mosque with the graves of King Faruk and Shah Mohammed Resas, the Ibn Tulun Mosque, the mausoleum of Shagarat el-Du and the Blue Mosque (Aksunkur Mosque) |

| Continent: | Africa |

| Country: | Egypt |

| Location: | Cairo |

| Appointment: | 1979 |

| Meaning: | one of the oldest Islamic cities in the world |

Islamic Cairo: History

| 969 | Conquest of Egypt by the Fatimids |

| 973 | Cairo capital of Fatimid Egypt |

| 1087-91 | Construction of the city wall with bastions |

| 1168 | devastating fire |

| 1175/76 | Reconstruction of Cairo and construction of the citadel |

| 1250-1517 | Economic center of the then Islamic world under the Mamelukes |

| 1335 | Construction of the El Nasir Mosque |

| 1517 | Conquest by the Ottomans under Sultan Selim I. |

| 1652 | Reconstruction of the Blue Mosque, damaged by earthquakes |

| 1798 | Napoleon’s entry into Cairo |

| 1805 | Entry of the Pasha of Egypt, Mohammed Ali, into the citadel |

| 1814 | Construction of the Gawhara Palace |

| 1823 | Destruction of the citadel by explosion |

| 1912 | Construction of the Rifai Mosque |

| 1992 | partial destruction by earthquakes |

A plea for a hated city

Clay and stone, concrete and asphalt, bustling bazaars and magnificent mosques form the mosaic stones that make up the Nile metropolis. Every day in this largest city in Africa with at least 15 million residents seems to be chaos rather than rules, especially when the majority of all cars registered in the country roll through the streets and alleys and their exhaust fumes pollute the air that is forced under a hood. The present does not treat the once reverently “El Qahira”, “the victorious” city, which was at times expanded into the most splendid metropolis in the Islamic world: the mosques in the old town – Ibn Tulun, El Nasir and the youngest, only created in 1912, Al Rifai, the great Khan el Khalili bazaar with its alley labyrinth. The alabaster mosque of Mohammed Ali was built in the 17th century and rises on the foundation of the citadel built in the 12th century. They are all architectural greetings from the heyday of Cairo, buildings that could have sprung straight from the stories from the Arabian Nights and could provide the backdrop for a Hollywood film adaptation of the stories of Sindbad or Ali Baba without any stage design intervention. And: the “victorious” on the Nile today has a dubious reputation. One can simply hate them, say some, or one succumb to their bitter charm without even having the chance to defend themselves, say others. Buildings that could have sprung straight from the stories from the Arabian Nights and could provide the backdrop for a Hollywood film adaptation of the stories of Sindbad or Ali Baba without any stage design intervention. And: the “victorious” on the Nile today has a dubious reputation. One can simply hate them, say some, or one succumb to their bitter charm without even having the chance to defend themselves, say others. Buildings that could have sprung straight from the stories from the Arabian Nights and that could provide the backdrop for a Hollywood film adaptation of the stories of Sindbad or Ali Baba without any stage design intervention. And: the “victorious” on the Nile today has a dubious reputation. One can simply hate them, say some, or one succumb to their bitter charm without even having the chance to defend themselves, say others.

In 969, according to cheeroutdoor, the Fatimids conquered Egypt and founded what is now Cairo – millennia after the pharaohs built their pyramids not far from here and three centuries after the city of Fustat was founded. For generations, year after year, minaret after minaret also stretched into the sky above the city on the Nile, where there was a building boom in the 13th and 14th centuries, the culmination of which was the construction of the El Nasir Mosque – each another minaret was an additional indicator of power and wealth, each new mosque a milestone on the way to the “capital of the Islamic world”.

Nowhere else do relics of 5000 years of history and the troubled present collide so harshly on almost every street corner, but nowhere else is the gap between the present and the “once upon a time” so small. Embarrassed, you feel your way up to this urban juggernaut, fight your way uncertainly through the colorful and loud bazaar Khan el Khalili, take in disbelief and grasp the silence in the large, rectangular inner courtyard of the Ibn Tulun mosque from the 9th century, after you only steps away from the gate, still being tossed by the noisy traffic. The curious gaze falls on the minaret with the spiral external staircase – a construction method that is unique in Egypt. If there was not a distance between politics and religion, it would be impossible for non-Muslims.

The architectural style of this magnificent building on the walls of the citadel is undoubtedly Ottoman and is reminiscent of Islamic sacred buildings in Istanbul. In 1830, Mohammed Ali had his mosque built on the ruins of the fortress destroyed by an explosion, the minarets of which tower 80 meters. Each of the numerous official and unofficial guides there directs their guests to the clock tower of the mosque. It is said that it was a gift from the French in return for the obelisk that now adorns Place de la Concorde in Paris: “The obelisk has been there for over a hundred years and the clock here too.” The clock alludes to a standstill, which, despite regular repairs, has to pay tribute to the drifting sand and the effects of the climate and returns to the »standstill of time«.